Dr. Greg Merz is hot on the trail of a killer. He spends most of his workday watching proteins interact with one another, usually eavesdropping on this give-and-take on his computer screen with the help of a cryo-electron microscope.

Merz, a 2010 Allegheny College graduate, conducts his observations and research at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF), and the killer he’s trying to put under wraps is the novel coronavirus.

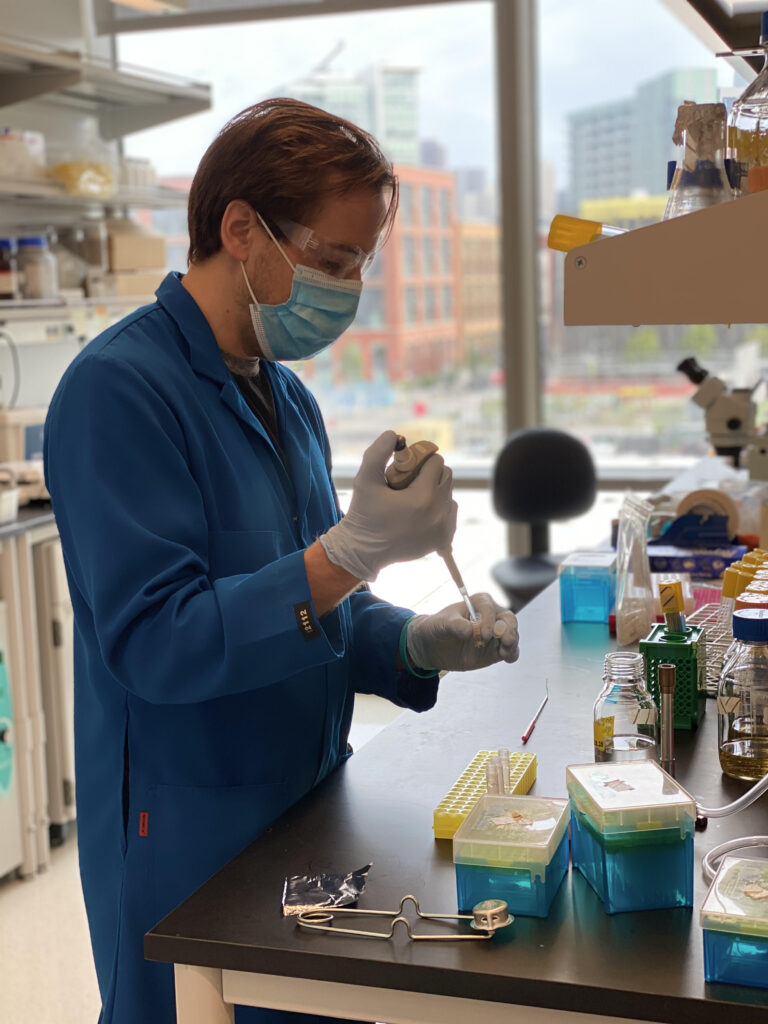

Dr. Greg Merz, a 2010 Allegheny graduate, conducts coronavirus research at the University of California at San Francisco.

Merz originally headed west after completing his Ph.D. at Cornell University. He wanted to get involved in research to develop therapies for neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. That was until this past March when he was called in to help develop medicines to curtail COVID-19. He is now a member of the Quantitative Biosciences Institute Coronavirus Research Group, which is a task force led by more than 20 faculty members and their research groups at UCSF. It includes experts in virology, cell biology, structural biology, computational biology and drug discovery.

“As a whole, we are focused on finding therapeutics for COVID-19, specifically by disrupting the replication cycle of the virus,” says Merz.

A virus replicates by forcing its genetic material into a host (human) cell, which is followed by the synthesis of viral proteins, Merz explains. Viral proteins interact with human proteins, and these interactions allow the virus to hijack host cells, which in turn allows the virus to replicate and spread. So far, the research group has mapped over 300 of these viral/human protein interactions.

“One main goal of the group is to design and develop compounds which disrupt key viral-host protein interactions, thereby prohibiting the virus from replicating and eliminating COVID from the body,” says Merz, who was a double major in chemistry and economics at Allegheny.

The group’s work was featured in an April 30 article in the San Francisco Chronicle that focused on the team’s valuable discoveries related to COVID-19 therapies.

“My specific research is in the Structural Biology Consortium or the structural biology subgroup. Our aim is two-fold: First, we want to understand in detail the structures of the viral and human proteins and how they interact at the atomic level — that is, which parts of each protein are interacting, and how are the individual atoms arranged in these interactions,” Merz explains. “Once we understand how these proteins interact structurally, we can design potential drugs to break those interactions and thus disrupt the life cycle of the virus. The second aim is to structurally characterize already developed potential drugs, in order to understand how they bind to their targets. This information is very useful for those designing and optimizing therapeutics, and can lead to greatly increased potency for already promising drug candidates.”

Merz is a member of one of the teams expressing proteins (protein expression refers to the way in which proteins are synthesized, modified and regulated in living organisms), and he also is on a group that oversees the collection and data processing for cryo-electron microscopy. “So I’m able to contribute at the beginning of the process and then again at the end,” he says.

Says Merz, who is originally from Rochester, New York: “On a very basic level, I wouldn’t be working on COVID research today if it wasn’t for my experiences at Allegheny. I developed my passion for lab work while doing summer research and then my comp under Dr. Marty Serra, and this set me on my way toward graduate school and ultimately my current post-doctoral position. One of the many insights that Dr. Serra taught me during my time in his lab was that it’s important to be able to communicate to a wide range of audiences. He was always adamant that we not only present to scientific audiences, but to the general public as well, and I really think this has served me well during the pandemic. (Watch Merz talk about how his Allegheny education has aided in his research by clicking here.)

“On a very basic level, I wouldn’t be working on COVID research today if it wasn’t for my experiences at Allegheny,” says Greg Merz.

“Being a double major also helped me to understand the non-medical factors surrounding the pandemic,” says Merz. “People aren’t only suffering because they are sick or know someone who is sick. Many have lost their jobs or are fearful about losing their job, are worried about paying the rent or providing for their families. Having a background in economics gives me a good platform to analyze the non-medical impacts COVID has had on our world, and analyze the balancing act of social distancing and keeping things shut down against getting folks back to work and the economy up and running again.”

Merz says that on most days he goes to work at the UCSF laboratory. “Obviously going to work is less safe than working remotely, but with lab work this is not an option,” he says.

Each person has to complete a daily health screen before coming to work on the UCSF campus, he says. “For transportation to work, we are not allowed to take any form of transportation where we might come into close contact with people outside of our own homes, such as public transportation, rideshare or carpooling. I have been biking to work, others drive themselves, and those who live close by walk,” says Merz. “I also think that maintaining mental health during this time is just as important as maintaining physical health, so I’ve been mindful of that as well. I’ve really been focusing on trying to get enough sleep and exercising on the days when I’m not biking to work.”

Merz says perhaps his toughest challenge is being able to “shut off my brain,” to stop focusing on work. “There is so much exciting research to be done, so many interesting ideas to follow up on, that you really want to be involved in all of it, when that’s not really possible. And there are so many talented scientists, from areas that I don’t know too much about, who push me by asking questions about my areas of expertise, or challenge me to learn new concepts, that I feel that I need to do a lot of learning to keep up. Not that I need any more of a push to work, but every day I’m trying to keep up with current events, and it’s been dominated by COVID coverage.”