Allegheny College graduate Manuella Mwihemuka personifies resilience.

Born in Rwanda, Mwihemuka survived her home country’s horrific genocide in 1994 and left Africa at age 13. She first enrolled as an Allegheny College student in fall 2007. Her Allegheny journey would culminate, some 13 years later, in her graduation with the Class of 2020 — and her acceptance to a master’s program in public administration/health.

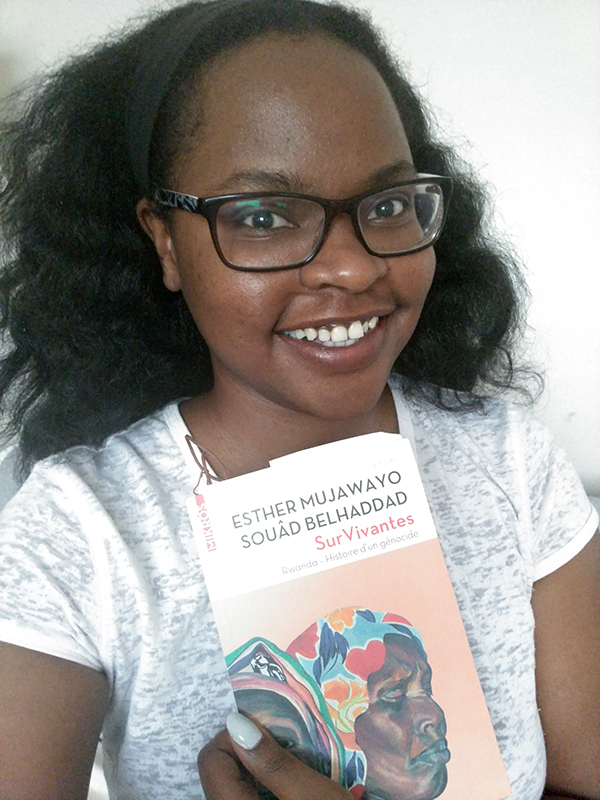

Mwihemuka majored in French with minors in political science and Spanish. Her Senior Project focused in part on SurVivantes, Esther Mujawayo’s account of Rwanda 10 years after the genocide.

Mwihemuka and her Senior Project Advisor, Professor of French Laura Reeck, chronicled their experience reading SurVivantes alongside each other during spring 2020. Following are their reflections on Mwihemuka’s experiences and her return to Allegheny to complete her degree — and the insights they gained as student and teacher.

[box]Manuella Mwihemuka: I had always known that I was going to finish my schooling at Allegheny. The process of returning to school was a long one. For a very long time I had been struggling with figuring out who I was, where my roots were and where exactly I belonged. I was struggling to understand my feelings, make a connection with myself, and fit into a world that sometimes did not make sense. Financially, I knew I had to pay off what I owed from the previous semester in order to return. That at least was a fact (or in my case an obstacle) that I could tangibly overcome. Amongst my first order of things was to find out the exact amount that I owed, and what I needed to do to complete school. Having accomplished that, I set out to find my first job, which allowed me to work from home, and searched for a secondary one because the first one would not be enough for me to pay off my debt and come back in time for the spring semester at Allegheny.

[/box]

[box style=”blue”]Laura Reeck: On April 6, under a stay-at-home order and continuing to teach from home, my students in “Francophone Societies and Cultures” and I began reading Esther Mujawayo’s SurVivantes (2004). As we read about the terrible unfolding of the month of April 1994 in SurVivantes, in which Tutsi survivor Mujawayo aims to raconter, témoigner, et accuser (tell, witness, and accuse), I was also reading Mujawayo with Manuella, who was completing her last semester at Allegheny as well as her senior project. I had known Manuella since she first came to Allegheny; she stood out with her force de vivre. When she took a leave from the college, I had a deep sense that she would return to finish what she had started. And that is exactly what she did in spring 2020. When Manuella and I began planning her return to campus, we also began talking about her comp, which would also focus in part on SurVivantes.

[/box]

[box]MM: Meanwhile, on an emotional level I was still struggling with… me. All of me. Asking myself questions of worth and value, and still searching for the understanding of self. At some point I realized that in order to figure that out I needed to go back into my past. I needed to open the door to some dark closets full of skeletons and demons, and purely and honestly let them out. I needed someone to hear me and hear what I was saying in order to help me figure out what was going through my head. I found the right professionals, willing to take the time to hear me. Hear the story of my youth in Rwanda, the story of our home being blown up, hear the witnessing of people being killed in our home and the corpses left there for us to bury. Hear how we left our home leaving my paternal grandfather behind because he decided he was too old to leave, and his home was where he had built it. Surviving traveling to the refugee camps hidden in between mattresses in the back of a truck… It’s funny as I write this, I realize I had never put it onto paper before. You see, we never talked about it. We just did not. And amazingly, more often than not, I was told I was too young to remember. And whether it is a lack of knowledge or understanding from adults, children remember. They may not always understand what it is that they remember, but they remember. In any case, I started from scratch and went back to my youth.

[/box]

[box style=”blue”]LR: As my students and I were reading SurVivantes, we discussed topics like the inaction of the international community as the genocide started, the reconstruction of individual lives after the genocide, the founding of Mujawayo’s foundation for widows AVEGA, and the difficulty in seeking and finding justice. As I was reading SurVivantes with Manuella, we discussed resilience, as theorized by French neuropsychiatrist Boris Cyrulnik, and the act of witnessing. Mujawayo calls herself a “transmetteur,” and in SurVivantes, she establishes a chain of transmission, beginning with her co-author, Souad Belhaddad, who listened and transcribed faithfully what Mujawayo told her in conversation, right down to marking pauses and silences themselves alive with meaning and emotion. But, also, Mujawayo recounts the stories of other women survivors, herself becoming a link in the same chain of transmission. It is an inclusive and enveloping account, one that drew Manuella into its fold.

[/box]

[box]MM: As I read Mujawayo’s account, I felt transported back to a world I had not explored in over 20 years. A world in a little corner of my mind, with only images, my personal thoughts and my language to remind me of it. I never wanted to lose my native language of Kinyarwanda. I felt as though I would be losing a part of me, losing my home. Ironic, isn’t it? Most images that I have from Rwanda are of death and destruction, and yet I don’t want to lose my language because I’d be losing my home. When I started reading Mujawayo’s book, a wave of emotions hit me. I cried. I had nightmares of being chased and someone wanting to kill me. For a straight week I did not sleep without having a nightmare. I felt angry. I felt disgusted. I felt discombobulated. I had to put the book down and pull myself together. I understood that for me this was part of the “final journey” to lay to rest a chapter of my life that had risen from its dormant state without my awareness. I also had a comp to finish. Where I could not physically go back to see and touch with my own eyes and fingertips, Mujawayo took me with her account. Revisiting the images that I had packed away in the corner of my mind, exploring feelings I didn’t remember having…

[/box]

[box style=”blue”]LR: An estimated 800,000 lives lost in three months — a number in a timeframe that defies the imagination, “la limite de l’inimaginable.” Mujawayo, who speaks decisively against all forms of censorship and self-censorship, spares no details. Despite the very difficult circumstances described in the book as well their difficult circumstances in the global pandemic, my students read on. The account concludes with a list of all of Mujawyo’s relatives who were killed in the genocide: it paints the picture of a family tree with no branches. A student offered that she saw SurVivantes as a figurative burial for all those killed during the genocide who had not had a proper burial or whose bodies had never been found. Another student expressed disappointment at the end of 300+ pages account that it did not have a happy ending. In the end, I offered that the happy ending was the materiality of SurVivantes — that the book exists today for Mujawayo’s daughters (to whom the book is dedicated) and as testimony to an important chapter in recent history. And, very importantly, writing the book — an act of completion — was part of Mujawayo’s journey to resiliency, much as Manuella’s comp was for hers.

[/box]

[box]

MM: Resilience is a word that I had heard a lot especially as I got older, however, I had never taken the time to learn what it really meant. When I first thought about a topic for my comp, I was looking to explore the effects of war on first- and second-generation survivors. Amongst email exchanges with Professor Reeck and personal exploration, I ended up at the threshold of trying to understand how two people can go through traumatic events and one of them comes out on the other side having survived and thrived, while the other falls off the wagon. It was also a search in trying to understand what kept pushing me to accomplish the journey I started at Allegheny. I wanted to feel alive. I knew that I was a fighter. I have always known that. I am a fighter, but I didn’t know whether I was resilient or not, and if I was, what exactly did that mean?

My journey has taken me to some dark places, places I wish I had not visited. My journey has also formed me to be a strong and resilient human being. There is no obstacle in this world that could be placed in front of me that I would not try to overcome. Finishing the comp, and completing my education at Allegheny, was not just a matter of doing it just because it was what needed to be done. It was important for me to lay to rest a past that had halted me in my own steps and almost drowned me in an ocean of unconscious living and empty life. Mujawayo validated my experience during the genocide of 1994. Even though I have had no one to talk to about it, reading her account and the account of others who have suffered has connected me to a lifeline. I now know that I can build life on a foundation that I have laid down and that my past doesn’t define me. It is a part of my story, a part of who I am. With putting my past to rest, I have the assurance that I will not pass down to other generations the hate and anger that had been festering inside of me for years because I allowed myself to face the turbulence of my youth and make peace with it. Writing my comp has allowed me to explore my experiences indirectly, more objectively, historically and explore my hypotheses with regards to what it means to be resilient. I was getting ready to step into a new and welcomed future…[/box]

Force de vivre. Resilience.