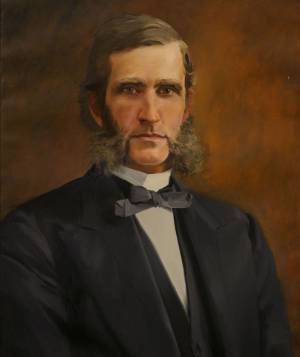

December 27, 1847-February 26, 1860

The Reverend John Barker was the only foreign-born president of Allegheny before the millennium. He also was the only president in that span to die in Bentley Hall. Barker further holds the distinction of being the first environmentally minded head of the institution.

Born in Foggathorpe, Yorkshire, England, on March 17, 1813, Barker immigrated at the age of three years when his family settled in central New York State. A scholarly youth, he graduated from Geneva College (now Hobart-William Smith) in Geneva, New York, by the time he was eighteen. He then taught private school for four years, during which period he joined the Methodist Episcopal Church and obtained a license to preach. He taught mathematics for five years at Genesee Wesleyan Seminary in Lima, New York, and accepted appointment as vice president and professor of natural philosophy and chemistry at Allegheny in 1840. He soon chaired the trustee committee that countered the complaints against the College submitted to the Pennsylvania Senate by Sophia Alden.

Barker gave the commencement address in 1843 and taught at the local academy in the ensuing months while the College was closed. Upon its reopening in 1845, he was in charge while President Homer J. Clark canvassed for funds. Disheartened by low enrollment, Barker left in March 1846 to teach ancient languages at Transylvania University; that institution soon granted him an honorary Doctor of Divinity degree, as did Washington College in Pennsylvania.

President Homer Clark’s resignation brought about the prompt election of Barker to the presidency of Allegheny. Warmly welcomed as a devout, pleasant, and humble person, he was a teacher at heart and reveled in the recitation room. As president he believed he should teach as much as the regular faculty; he therefore assumed a heavy load. As executive, the small, sprightly, and gentle Barker governed more by love than by fear. His term was characterized by harmony and little change among the faculty. Concerned by the starkness of the campus, he encouraged arbor days, during which students planted trees and shrubs brought from the neighboring woods. Undergraduates poked fun at Barker’s eccentricities but adored him for them. The students estimated he could speak extemporaneously on any subject. It was said that if Barker came to class rubbing his hands, the learners knew they would receive apt illustration and witty comment. If he approached with thoughtful stride and hands behind his back, they steeled themselves for a session of tough, probing questions. Barker read widely and possessed a retentive mind. Personal charm, joined with a broad range of knowledge and interests, made him an exceptional conversationalist and adviser. His playful wit enabled him to induce laughter from any audience. He brought a new style to the presidency and gave the College a congenial aura before students and community.

During these years nearly all the faculty and many students supported the Know Nothings, a secret party that opposed the alleged political influence of Roman Catholics and immigrants and locally, at least, criticized slavery. As an immigrant, Barker was excluded. On the hot sectional issues of the day, he was conservative. Barker feared that northern attitudes, John Brown’s raid at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, and the abolitionist sentiments within the Methodist Episcopal Church would jeopardize national and ecclesiastical unity. His plan to argue against extremism at a General Conference of the Methodist Church was cut short by his death.

During Barker’s tenure, the number of students increased, though the majority were preparatory students and attrition remained high. Classical and Biblical studies received extra emphasis; offerings in science and modern languages were spotty. Completion of Ruter Hall in 1854 finally provided the College with sufficient new space to enable Barker to move his family into the east wing of Bentley Hall. He later shifted the family rooms to the west wing, where he died early on February 26, 1860, following a stroke he endured while critiquing essays in his chamber the preceding evening.

* This account is taken with permission nearly completely from J. E. Helmreich, Through All the Years: A History of Allegheny College. Meadville, PA: Allegheny College, 2005.